Photo by Nancy Howard.

by Christine Kreyling

The romantic language often applied to The Sea Ranch, CA typically evokes places of the imagination. To wit: “The Dream of The Sea Ranch” (film, 1994), “Utopia by the Sea” (New York Times, 2008, The Magic of The Sea Ranch (book, 2011), “a land so sublime” (The New Republic, 2011).

In more prosaic terms, The Sea Ranch is a planned-unit-development roughly bisected by California State Route 1 about three hours from San Francisco in the northwest corner of Sonoma County. Like many residential developments of the mid-1960s, it arose from the subdivision of farmland, is composed overwhelmingly of single-family homes, is car-dependent and lacks a grocery or other commercial offerings necessary for daily life. The street system also suggests a 60s suburb; it lacks interconnectedness, with many streets terminating in cul de sacs and feeding traffic onto an arterial.

Prosaic, however, doesn’t do justice to “land so sublime.” The Sea Ranch lies on ten miles of the austerely beautiful Pacific north coast, with rocky headlands thrusting into the sea, bleached-tan meadows and the greens of firs, pines, Monterey cypress and redwoods. The Ranch’s approximately 3,600 acres, reaching inland from a half-mile to a mile, rise from ocean bluff through grassland terrace to forested ridge. This is the stuff that dreams are made of.

Dreams of the 60s, however, have usually arrived in the 21st century in a battered state. As The Sea Ranch approaches build out—1,800 of the 2,284 lots have houses—and celebrates its 50th birthday, it’s appropriate to examine how much of the original vision has survived later encounters with realities.

The First Dreamer

This early 1970s photo depicts the southern coastline of The Sea Ranch, with Condominium One in the foreground and the Sea Ranch Lodge behind it. Note how barren is the site, with the Monterey cypress hedgerows as the defining landscape element.

Courtesy ©The Sea Ranch Association.

Al Boeke initially saw what was then an overgrazed sheep ranch during a 1962 flyover. The breadth and character of the landscape prompted the architect-turned-developer to suspend his search for a “new town” site on behalf of Oceanic Properties, Inc. and lay plans for a second-home project for the Hawaii-based corporation. As Boeke described in a 2008 interview by architectural historian Kathryn Smith, he spent five days walking the site. He saw newly dropped lambs, wild iris in bloom, and seals sunning on offshore rocks that were themselves “like giant animals.” The “cathedral-like columns” of Monterey cypress, planted perpendicular to the shore in double rows as windbreaks in the early 20th century, were especially striking. These so-called “hedgerows’ were then the most significant manmade design on the land. “I became emotionally involved with The Ranch during those five days,” he told Smith. “And that’s never left me.”

Having found a place that, in his words, wasn’t “corrupted by the wrong—the mistakes of others,” Boeke resolved not to despoil it. “My basic notion” was that “we would respect the land,” he said. “We would put people on the land in a way that they were inconspicuous. We would build architecture that was not architectonic, that seemed natural in this place. And we weren’t going to build a recreational community for destination and play, but a quiet, meditative community for ‘just folks,’ as I called them.”

Boeke died at his Sea Ranch home in 2011, embittered by The Ranch’s failure to live up to his vision. “This isn’t any longer The Sea Ranch, as far as I’m concerned, and that’s a pretty rough statement,” he told Smith.

Mistakes Were Made

It’s true that The Sea Ranch has seen its share of “mistakes.” These include significant departures in site planning from the original master plan concepts.

Participants at an October forum marking the 50th anniversary, “The Once and Future Sea Ranch,” pointed out the devolution from early development patterns at the south end as planning moved north up the coast. They criticized the generic suburban character of the later build-out. “It’s not about the [greater] number of units,” said landscape architect Linda Jewell. “It could have been the same number of people. It has more to do with the loss of quality, of subtlety in the development: how the roads were put in, the houses sited, the grading, the loss of connection from the meadows to the [bluff] edge.”

Blame has been cast on loss the developer for losing faith, on quick-profit-seeking real estate brokers, on misguided environmentalists. There’s enough truth to go around. But it’s also true that reality has a way of eroding visions.

Inserting Man into the Landscape

Boeke held positive meetings with Sonoma County officials to test their support for his development plan, which involved an average density of one housing unit per acre. He then convinced Oceanic to proceed with what was initially called the North Coast Ranch. In 1963 he hired a team of consultants, headed by landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, with whom he’d worked on a new town in Hawaii.

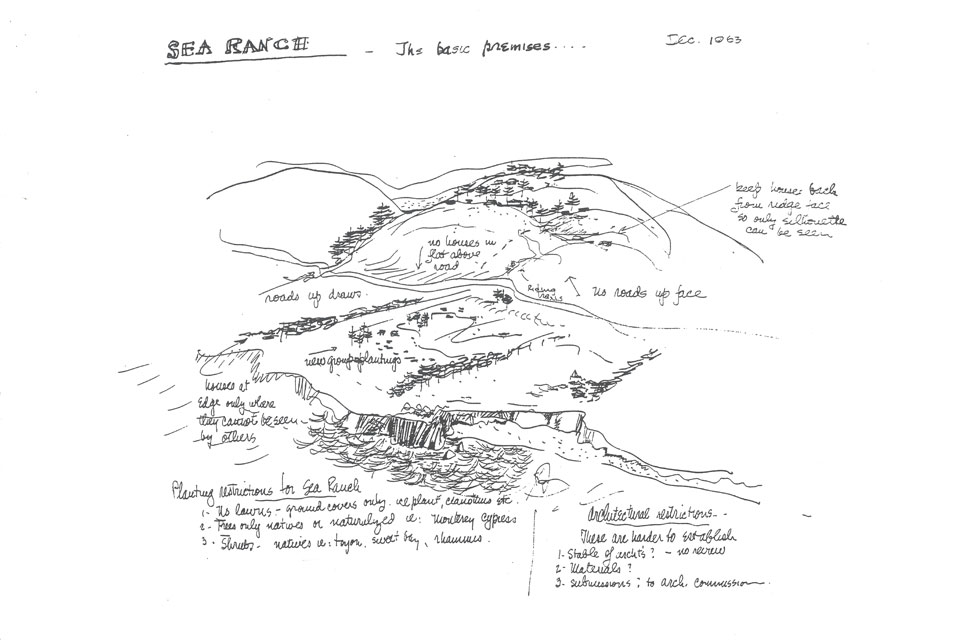

This 1963 drawing by Lawrence Halprin illustrates the landscape architect’s desire to work with and preserve the land by minimizing the visual impact of human presence. Credit: Lawrence Halprin Collection, The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania

Halprin was determined to work with the land rather than engineer against it. This philosophy of landscape design was part of the broader American environmental movement, then in its first wave.

As Jewell explained during the forum: “Larry [Halprin] and [Ian] McHarg and all the leaders of that era were saying: ‘We’ve got to understand how the landscape works in order that that we can insert ourselves, because we’re going to insert ourselves anyway. But we want to insert ourselves understanding the implications of how we do it, and hold on to as much as we can of the [natural] experience.”

This 2014 photo of Black Point Prairie at The Sea Ranch shows how Lawrence Halprin’s 1964 site design clustered houses against the cypress hedgerow, away from the bluff edge, leaving the meadow as commons with views open to all. Photo by Nancy Howard.

Boeke specifically tasked Halprin and the rest of the team to devise an overall site plan, a schematic for the south end to include lot and utility layouts, and detailed plans for demonstration homes. According to historian of landscape design Kathleen John-Alder, memos from Boeke to Halprin also “called for the discreet accommodation of cars, and buildings clustered around preserved common land, which, Boeke argued, would distinguish the Sea Ranch from its ‘suburbanized” California competition.’ Above all, though, Boeke was a realist; he expected the design to ‘remain flexible’ and not ‘too explicit’ before market testing.”

To retain flexibility and even out cash flow, Oceanic would submit separate plats for each “unit” of the site according to the sequence of development. Each would be annexed to The Sea Ranch after approval by Sonoma County.

Boeke focused on the south end of the property for initial development efforts. According to John-Alder, “The environmental sensitivity of the southern area”—steep slopes to the east and wetlands dotting the western side—“necessitated a low density that both conveniently reduced cost and exploited the marketing potential of the beautiful setting. Density would then increase along with financial obligations as the project moved north, toward the river and town of Gualala. This fiscally shrewd buildup was to culminate in a pedestrian-friendly village. The Sea Ranch, Boeke observed, would evolve and ‘adapt itself to time, and change in the market, and change in need.’”

Studying Before Building

To understand how the Sea Ranch landscape worked, Halprin commissioned a series of studies: ecology and landscape, soil mapping, sun and wind patterns, a forest survey, fire risk, the watershed and the potential impact on it of runoff from roofs, paving and forest thinning.

Ecologist Richard Reynolds submitted a report on “Important environmental factors relevant to site planning on The Sea Ranch.” Reynolds recommended mitigating wind force by thickening existing cypress hedgerows, and planting new ones, especially in the north end, where the hedgerows were widely spaced.

Because the climate is cool and shade provision unnecessary, structures should be designed to maximize passive solar by means of southern orientation and specific roof pitches. The drainage plan should redistribute water evenly over the land rather than concentrate in one place. Engineering obstructions to the natural watershed should be minimal.

The Master Plan

The team met for over a year, translating the findings into development concepts, site plans and structure designs. Lots for single-family homes were carefully tucked into the wind protection of the cypress hedgerows and placed away from the bluff edge at an angle to the shore, leaving meadows open and enabling all to have ocean views.

The narrow and treeless land at the extreme southern end was planned for a series of condominiums, organized around wind-protected courtyards. Here the architecture would reinforce natural landforms rather than blend into them. Lots on the eastern slopes were sited so housing didn’t extrude beyond the forest edge to reduce its visual impact.

Because curb-and-gutter infrastructure would interfere with the sheeting of runoff, it would only be used to prevent erosion on steep slopes. There would be no streetlights to disturb nocturnal wildlife.

Real estate attorney and team member Reverdy Johnson developed “Covenants, Conditions and Restrictions” to translate planning concepts into reality from the standpoint of land use regulation, whether public under zoning and subdivision ordinances, or private by way of restrictive covenants. These CC&Rs, in 50 pages of provisions, established The Sea Ranch Association of homeowners, the Design Committee for architectural review, and the commons as owned by all association members.

Encounters with Reality

Market Forces

After this initial planning effort, and considerable investment by Oceanic in infrastructure and model housing, sales of lots were brisk. The stars seemed aligned for a smooth build out. Boeke began to cut costs by switching from consultants to in-house planning and design staff.

Halprin did his last plans for Oceanic in 1966. Boeke left the project in 1969 to explore new towns for Bechtel, but not before the master planning concepts began to give way. Housing sites crept into grasslands, onto the bluffs and out of the forest, maximizing views for some and lot sale profits for Oceanic.

Condominiums, which had been a central strategy for attaining financially- required densities without gobbling up land, disappeared from south end planning maps. The Halprin team’s 1964 “Development Plan of the Southern Portion,” covering 1,800 acres, included 141 acres for 846 condo units. By 1969, despite the instant architectural fame of Condominium One (1965), “The Sea Ranch Composite Map” for the southern half contained no lots specified for condos. The 1972 “Sea Ranch Composite Map” contained five condo sites for the higher-density north end, but none were built. Today The Sea Ranch has two condominiums containing 14 units.

“There was little market for condominiums,” real estate attorney Johnson explains. Condos were a new phenomenon on the market and had been built primarily in Southern California in a cheap fashion. “They weren’t associated with quality.”

Oceanic thought that other developers would buy land “to do the high-density stuff, clusters and condos,” Johnson explains. “That didn’t happen. So Oceanic was faced with selling single-family lots or doing the bricks-and-mortar themselves.” Oceanic tested the market by building clustered housing in Unit 29 in the early 1970s. “They had a hell of a time selling 29. It’s a lot simpler to sell a lot-with-a-view.”

These Madrone Meadow Clusters houses, developed by Oceanic Properties, Inc. beginning in 1972, were the last of the demonstration units built by the developer to illustrate how to build on the land. Part of Unit 29-A, along with the White Fir Clusters and the Walk-Ins, these houses were the first to utilize sewers rather than septic for wastewater disposal. Photo by Jim Alinder.

The “coastal village” combining commerce and dense residential proposed by Halprin for the north end also fell to real estate logic. This concept was nixed after a 1969 report by Economic Research Associates found weak market support. E.R.A. predicted that Oceanic costs would include not only construction but also subsidies to merchants for a considerable time before the village could become self-sustaining, much less profitable.

Personnel changes at the top of the corporate structure also had their impact on Sea Ranch development, Johnson says. These changes filtered down to site planning at The Sea Ranch.

By way of example, Johnson points to Unit 28, annexed to The Sea Ranch in 1970. Here the land is relatively flat, the flanking hedgerows broadly spaced. Foregoing a more nuanced approach, the planner filled the meadow with five double-loaded corridors of lots. According to Johnson, the project manager for The Sea Ranch at the time of this “huge error” was a retired Lockheed engineer. “He didn’t know squat about real estate. But he knew about engineering and Unit 28 is an engineer’s’ dream. Looks like a nervous system with ganglia.”

Oceanic also wavered in its commitment to environmentally sensitive planning. The developer largely ignored a 1971 report by Planning and Research Associates on “Relative Development Suitability” of the remaining open land that cautioned against building in areas identified with potential soil instability. By this time Oceanic had a more compelling, government-regulated reality with which to contend.

Changing the Rules

During initial planning and development, wastewater disposal was predicated on the use of private, individual septic systems. Lots were sized to provide for leachfield construction and a 50 percent reserve area. Individual owners were responsible for gaining Sonoma County approval for their systems. Property owners whose lots failed percolation tests were allowed to use Sea Ranch commons land to comply.

Concern over more stringent wastewater requirements heading down the state and county government pipelines led Oceanic to plan to utilize sewer systems and sewage treatment plants for units annexed after 1969.

The switch to sewer increased Oceanic’s infrastructure costs but also the land’s density potential. And the use of sewer systems required less acreage for commons, which no longer had to play back-up for leachfields. The response was to maximize sales with more lots in more desirable locations, and dedicate less broad acreage to commons. Thus the 1972 “Sea Ranch Composite Map” features the north end layout forum participants decried: houses throughout the meadows, with streets terminating in a fan of oceanfront lots.

Attack of the Environmentalists

Major oil spills and the threat of nuclear power plants on the California coast, coupled with a rising tide of incursions by subdividers, galvanized environmentalists to pass Proposition 20 in 1972 to protect coastal resources from degradation. This created regional coastal commissions, charged with regulating and issuing permits for all coastal development.

The North Central Coast Regional Commission went after The Sea Ranch. Commissioners raised concerns about the amount of traffic a built-out Sea Ranch would belch onto Hwy. 1, the impact of Sea Ranch septic systems on the watershed, the lack of affordable housing. The sticking issue was public access to Sea Ranch bluffs and beaches. A virtual moratorium on building at The Sea Ranch ensued.

Oceanic and The Sea Ranch Association, used to being lauded as leaders in environmental planning, recoiled with shock—and litigation. Eventually the state passed legislation to resolve the dispute and allow building to resume at The Sea Ranch in 1982. But the developer and association had to make concessions: five public access trails, 15 view corridors from Hwy. 1 and 45 affordable housing units. Most telling from a fiscal perspective, the resolution required a reduction to a maximum of 2,329 residential units, a decrease of 55 percent in the average density Sonoma County had originally approved.

Public access accommodations have had no noteworthy impact on life at The Sea Ranch. But the reduction in density intensified fiscal pressure on the developers, who had no income from The Sea Ranch and heavy carrying costs in interest and operating cash flow during the moratorium. To decrease density and recoup losses, Oceanic replaced the remaining condo sites in the plan with single-family lots lining the bluff. Ironically, this degraded the scenic values so important to the environmentalists.

Later site planning abandoned Halprin’s early condos-and-clustering concept in favor of single family houses lining the bluff, which blocked ocean views from houses located behind the bluff-dwellers. Open space was also divided into less expansive segments, with the meadows losing their connection to the bluff edge. Photo by Nancy Howard.

Unit 35E, 1986. Unit 35E features houses lined in walls along the bluff on a site once intended for condos.

Unit 28, 1970. Unit 28 has double-loaded corridors of houses reaching into the meadows.

Unit 1, 1965. Unit 1, designed by Lawrence Halprin, features houses perpendicular to the coast and away from the bluff edge, with expansive commons between the rows of lots.

These depictions of various Units in the Sea Ranch site plan illustrate the chronological departure by Oceanic Properties, Inc. from Lawrence Halprin’s original 1964 concept plan.

Credit: Ron Yearwood, from site map by Mike Lane, ©The Sea Ranch Association

“Time eroded the original concept of a tight coastal community surrounded by open space,” Boeke told Tom Mikkelsen of the Coastal Conservancy in a 1985 interview. “Time and then regulation affected cash flow. Negative cash flow makes decisions—after a while, all of the decisions.”

The Fresh Green Breast of the New World

The Sea Ranch began during an idealistic era, when a return to Nature still seemed possible. By 1983 Halprin still hadn’t abandoned those ideals. The Sea Ranch’s “basic premise was, and still is, utopian,” he said in an interview by Sea Ranch resident Bill Platt. “I believed that we could make a place like those in which primitive peoples lived in a landscape without destroying it, were sustained by it, and made a life interactive with it.”

From 21st century hindsight, it’s easy to dismiss such talk as “naïve, even fantastical,” as urban historian Mitchell Schwarzer said during the “Once and Future” forum. The form of The Sea Ranch, with its cul de sacs, dispersed housing and car dependency, no longer seems sustainable. And today there’s rampant evidence that when we “insert” ourselves into nature, we alter nature for the worst.

The belief of Sea Ranch pioneers that they could create a utopia by the sea

was given special urgency by the place where they were standing when they dreamed: on the western edge of the North American continent. Behind them lay the landscape dystopia of the American suburb. Here, on land that Boeke envisioned as uncorrupted by the mistakes of others, was a chance, maybe the last chance, to get it right and show others how to do it.

F. Scott Fitzgerald described the feeling for all time in the closing passages of The Great Gatsby, which, despite its Long Island setting, he called “a story of the West, after all.” Al Boeke could have been Nick Carraway, who gazed out toward the Sound: “As the moon rose higher, the inessential houses began to melt away until gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors eyes—a fresh green breast of the new world. . .man must have held his breath. . . face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate with his capacity for wonder.”

©Christine Kreyling. A version of this article appeared in Planning magazine, March 2015.